Beginnings

In a world where everyone who owns a smartphone is a photographer, you may wonder why some of us pursue photography as a profession, and how we got there.

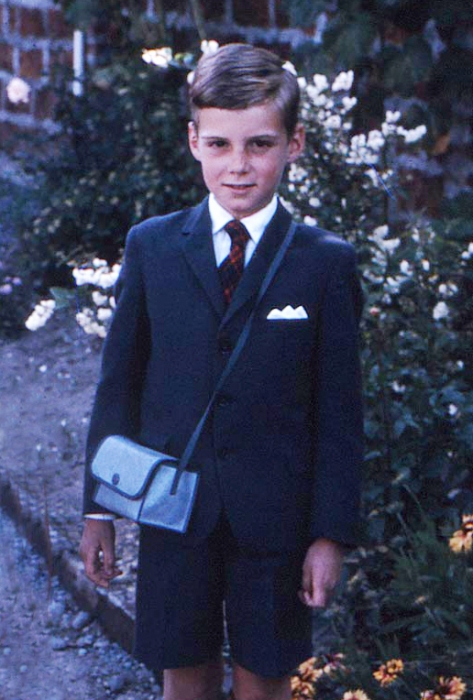

Do you remember the first time you took a photograph yourself and saw the results of your own handiwork? For me it began in the 1960s, growing up in Chile, when I became the proud owner of a Kodak 120 Brownie box camera. It was a present and I must have been 9 or 10. I remember it came in a smart, grey plastic carrying case (the whole camera was plastic, including, I think, the lens). I used to carry this camera proudly slung about my neck just about everywhere I went, especially when traveling.

There was a darkroom at school and soon I was developing and printing my own black and white photos. Oh, the anxious waiting to take the film out of the tank after fixing and washing, and hold the still wet roll of negatives up to the light to see if my precious images were OK…correctly exposed…sharp…printable. And then the careful dodging and burning in of the image onto the paper under the enlarger to make the perfect print. All black and white of course, and done under a dim, red “safe light” so that the paper would not be exposed to light. Some of you have experienced that joy. There are shades of it when you edit a photo in Photoshop or some other editing software and make it look the way you saw the original scene.

First photography “job”

Then came my first photographic job: official photographer for the school magazine. My young heart would swell with pride when I saw my efforts appear in print every month and I showed my parents and friends what I had created.

All through school in Chile and then in England, and in my early adult life, photography was a hobby, albeit a serious one. I always had my camera with me (I had graduated up to a 35mm rangefinder camera with two interchangeable lenses – a reward from my keen photographer father for winning a scholarship to the boarding school in England where I was to continue my education. I shall always be grateful for that gift. It was a wonderful camera.) At school in England I participated in the school photo club, displayed my somewhat unorthodox photos (avant-garde I used to like to think) in exhibitions attended by parents and teachers who nodded and grunted in dubious approval at my masterpieces. I spent hours in the darkroom inhaling toxic chemicals and getting my fingers stained, all to create my art.

When on family vacations I would wander off with my camera, trying to capture aspects of the place we were visiting that others did not notice. We went to the Algarve in Portugal when it was still relatively unknown, and while the others were tanning themselves on the beach, I took to the local farm roads with my Kodak Retina IIIC. I remember the sheer joy of coming across an old lady all dressed in black leading a small donkey laden with firewood down the lane. Click…click. (I was economical with my shots in those days, film was expensive). Careful composition, the right exposure. Focus. Fantastic. Of course I had to wait a couple of weeks to see the results, but the developing and printing of the film was just as exciting as taking the photos in the first place. One of them was perfect. When I showed my family the prints they were astonished that they had been in the same place and not seen anything like that. They had been busy with the ice cream and the bathing.

Transition from amateur to pro

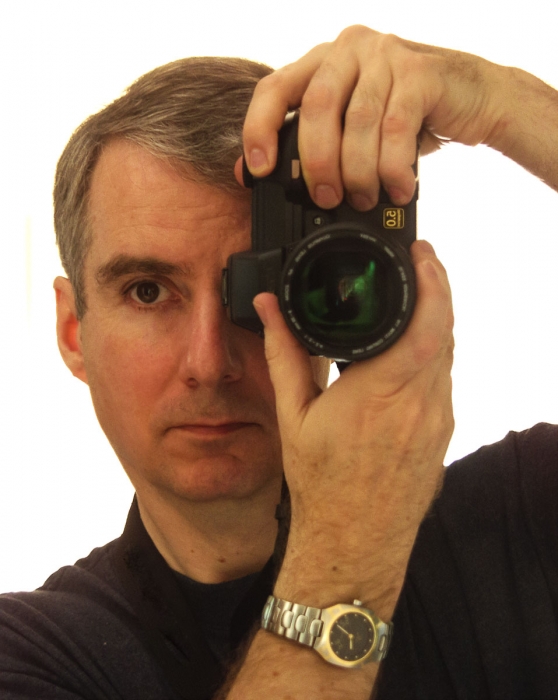

I didn’t graduate to the rarefied level of professional until the mid 1980s. After school I spent many years as a volunteer social worker of sorts. Now I needed to find a job. Photography was what I most enjoyed doing in life. Why not earn a living doing what you most love? I’m sure you have had the same thoughts and, I hope, have followed those dreams.

After serving an apprenticeship in a portrait and wedding studio (never again!) I decided to set up as a freelance, selling stock photos and working on assignment. It was a quantum leap for me. I remember taking my portfolio of black and white prints and Kodachrome transparencies to Bill Rosencrantz, in charge of the photo department at Harcourt Brace Jovanovich in Orlando, then the leading publisher of school textbooks. He placed one of my sheets of 35mm slides on his light table and leaned over them, loupe to his eye, to take a closer look. I was holding my breath. “Hmmmm. Nice shots,” he said, a bit hesitantly (he was a photographer himself). “But quite a few of them are soft. We’re only interested in pin-sharp photos.” This was an eye-opener for me. I had carefully chosen my very best images for this first portfolio presentation.

He did give me a trial assignment “on spec” which turned out well, and I went on to do hundreds of assignments for HBJ and other book publishers who needed set-up photos for their textbooks. But that day when I got home I pulled out my own loupe and studied all my slides (which I had thought were perfect) and saw what he meant. Some of my most cherished images were not really sharp at all. Ouch! Perhaps you’ve had a similar experience. You thought something was of a professional standard and then had a wake-up call which changed your whole view.

This was the first of many lessons. I had never done any formal photography study or training except for the New York Institute correspondence course, which was helpful in giving me an overview of the field but did not teach me what I needed to know to become a pro. I was, and am, entirely self-taught This goes for writing too.

There were a series of steps and milestones, each of which removed me further from the level of “good amateur” to that of “working, earning, professional.”

My heroes

My heroes were, and still are, the photographers of the 1950s, 60s into the 70s who made the original Life Magazine so popular. In days when TV was either not yet in existence or far less prevalent, the picture magazines were the way people saw what the world looked like. Photographers such as Alfred Eisenstaedt, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Margaret Bourke-White, Werner Bischof, W. Eugene Smith (the ultimate master of the photo essay), Robert Capa, David Seymour (Chim), Gordon Parks, Andre Kertész, Ernst Haas (another major hero for me) – I taught myself to see and photograph largely by carrying large bundles of their books back from the public library and studying the magic they created with their cameras. National Geographic was another key source of inspiration, though I must admit I don’t really like all those close-ups of bugs and beetles, and life without full-frame photos of sharks’ gaping jaws is fine with me. I still have many of those books, as well as the entire National Geographic on DVD, and pour over them from time to time when I need to recharge the creative batteries.

The ability to capture the essence of a scene, the intrinsic personality of a person, the drama of an event, and to tell a story – these are the key for me. When you can notice things that others don’t and show them, you have opened their eyes. Next time they might notice.

For love or money

I started off in editorial and stock photography and soon added writing to my repertoire. I particularly enjoyed photographing and writing articles for children’s magazines such as Highlights for Children, Sesame Street, Electric Company, and for general interest publications such as Grit and News and Views. I met some wonderful people and delved into areas of life that were completely new to me, such as the time I was working on an article for Native Peoples magazine and spent some time among a Seminole tribe in southern Florida who had never surrendered to the US government and still considered themselves to be a sovereign nation. But that was just one of hundreds of examples.

Then I found out that for the same work I would be paid far more in the field of corporate photography and writing, so started working for Hewlett Packard, Xerox, the airlines, even British Gas, John Deere, Miller Electric and many others. You probably know what it’s like to “follow the money” instead of following your passion.

However, there was a common denominator to all the work: telling a story through photographs or words and photographs.

Back to passion

Eventually the wheel kept turning and I came back to my earliest reasons for loving photography. It is a way to open people’s eyes to their world, get them more interested in their world and the people in it. Make them smile by showing something in a different light, something astonishing, something beautiful, a humorous moment or juxtaposition. When I travel and photograph and write about the places I have visited, and publish a book, I am satisfied when I hear comments such as, “After seeing your photographs/reading your book I just can’t wait to visit Paris, Cornwall, Peru, Bhutan – (fill in the blank).”

Today’s world

The technical playing field has been considerably leveled. I used to get jobs because I understood how to light scenes with strobes or correct color by use of a color meter and gels, had equipment others did not have, and so on. Now the level of sophistication of digital photography technology has made much of this redundant. Take the latest iPhone for example.

But it is not the equipment or even the technical skill that counts in the long run. They are necessary. But more important than these factors is the vision, the creativity, the purpose, the eye of the photographer.

I am happy to find that there is still a place for the professional photographer and writer in this much photographed and blogged about world.

That’s why these days I concentrate on photographic books and fine art photography. I hope to keep enlightening people about the wonders of the world we live in and the people who share this planet with us.